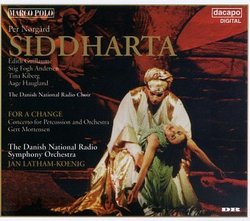

| All Artists: Norgard, Latham-Koenig, Danish Natl Radio Sym Title: Siddharta Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Marco Polo Release Date: 9/19/1995 Genre: Classical Styles: Opera & Classical Vocal, Forms & Genres, Concertos Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 730099973120 |

Search - Norgard, Latham-Koenig, Danish Natl Radio Sym :: Siddharta

| Norgard, Latham-Koenig, Danish Natl Radio Sym Siddharta Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSimilar CDs |

CD ReviewsWhat Pleasure is Built on the Pain of Others? Christopher Forbes | Brooklyn,, NY | 10/02/2003 (5 out of 5 stars) "Per Norgard's second venture into musical dramatic territory was perhaps as much "of it's time" as his first. Where Gilgamesh was very much a multi-media piece with the character of a 1960s happening, Siddhartha is a return to tradition, both to traditional concepts of staging and drama, and even to a more traditionally tonal concept. However, sunk deep within the music of the third act, are some of Norgard's most individual writing and an indication of the next period in this fascinating composer's output. Siddhartha continues Norgard's mystical interests and examinations of crucial points in human history. Interestingly, Norgard spends his time in this opera on the early life of Siddhartha, beginning in the first act with his miraculous birth and the prophecy that he would either become a great king or the savior of the world. In an attempt to keep his son attached to worldly pleasure, his father decrees that all the sick, infirm or deformed should be locked in a dungeon under the palace. The second act deals with Siddhartha's budding sense that all is not right, though his marriage to Yasodhara lulls him back into his world of pleasurable illusion. Finally in the last act, the facade falls away as Siddhartha witnesses illness and death first hand and the millions looked away in the dungeons are let out once again. After a crisis of sanity, Siddhartha realizes his destiny is to find a way for all beings to be released from suffering and he leaves the palace forever. The libretto, written by esteemed Danish poet Ole Sarvig, is full of lush imagery. The central image of the opera, the palace of pleasure built on the unseen suffering of the millions, is extremely powerful. This powerful verbal and visual image is reinforced in Norgard's brilliant music. Siddhartha is Norgard's final extension of his 1970s neo-romantic period. All material in the opera is developed from manipulations of the composer's famed infinity series...a sort of musical fractal procedure, which creates, and endless series of varied and yet related melodic patterns. Rhythms are calculated from proportions based on the Golden Section. The result is anything but mathematical. Rather the score, particularly in the first act, is lush and sensuous, as befitting the illusory pleasure palace constructed for Siddhartha's benefit. As the work continues, the music gains a darker edge, until in the last act; Siddhartha's madness is suggested by wildly swinging musical moods and violently dissonant passages. The final bars of the opera introduce material that is radically new, symbolizing the hero's journey into a new world of possibility. One of the things that impress so much about this opera is that Norgard and Sarvig don't attempt to create "spiritual" music in the sort of New Age way that is popular now. This opera is spiritual, but it is a spirituality that recognizes human pain, rather than trying to anesthetize it. The central philosophic question, how can one remain unpricked by conscience when all the beauty one enjoys is at the expense of the pain of others, is as Western as it is Eastern. There is no, "Eastern retreat from the world" in the opera. In fact, Norgard and Sarvig seem to understand that the European concept of Buddhism's "retreat from the world" is an incorrect understanding of the religion, which is motivated from deep engagement with the suffering of humanity, not retreat from it. As a result, this opera is more honest, more deeply felt, and moves one more than many other works that wear their "spirituality" on their sleeves. Highly recommended." Norgard's most ambitious opera and the summation of his 1970 Christopher Culver | 05/17/2009 (4 out of 5 stars) "The 1970s saw Danish composer Per Norgard developing a "hierarchical music". Here the melodies were formed by the infinity series, a fractal-like line where the same patterns appear at scales both large and small. His harmonies were based on the natural overtone series, the very stuff of sound itself. And his rhythms were fit to the golden section, that "divine proportion" found in much of nature and human art. These three together formed music of infinite expansion but complete cohesiveness, and when they appear in Norgard's masterpiece Symphony No. 3 of 1975, they seem to laud the very unity of the cosmos. But as the 1970s wore on, Norgard increasingly sought to express both the joys and sorrows of life. The opera "Siddharta" (1974-1979) is both the culmination of the hierarchical phase and a glance ahead to violent polarities in his later music.

Siddharta is the Indian prince who, prophesized to foresake the world, is locked up by his father in a pleasure garden far away from sickness, old age, and death. Eventually he discovers the truth of his existence, and heads out alone to find enlightenment. Norgard's music to a libretto in collaboration with Ole Sarvig closely fits the story. In the first act, revolving around the birth of Siddharta, the music is entirely based on the infinity series. This is music of heartbreakingly beautiful melodies, lush orchestration, and elegantly danceable rhythms (Siddharta's mother Maya is represented by an unspeaking ballerina). At the close of this act, Siddharta's father throws the community's cripples in the dungeon and order the construction of a sanctuary for the prince. Act II then opens with a simple modification of Norgard's hierarchical music: the harmonies are inverted. At first, the listener doesn't notice anything, thinking it a continuation of the first act, but soon one feels that something is wrong. The pleasure garden in which the prince grows up is a lie, just as the beautiful music is based on a distortion of the universal truths of hierarchical music. The dramatic tension of this act is formed by his father's insistence that he enjoy himself and marry a sexy princess, and his aunt Prajapati's protest that this deceit is wrong and that Siddharta must be told the truth. In final act, Siddharta finally discovers what his father attempted to hide from him, and repulsed by life's suffering he leaves the palace, little knowing where go is going. The opera closes with light drumbeats unlike anything heard before. You'll need to follow with the libretto the first couple of listenings even if you speak Danish, as often several characters are talking at the same time. While some might see this as a sign of operatic ineptitude, Norgard is a composer whose work has always been about interference, and the listener can concentrate on a different strand on each successive listen. This is an excellent opera, and a key work in Norgard's output. The liner notes are generally informative, as they include Norgard's theoretical explanation of how he derived his motifs, his reminisces about collaborating with Sarvig, and a brief essay on Sarvig's career. However, I was unhappy with other aspects of the production. Though this recording is of the Danish performance where Norgard wrote a new section inspired by the schizophrenic Swiss artist Adolf Wolfli, the liner notes make no mention of this important chance. The sound quality, while nowhere near as bad as on Dacapo's recording of Norgard's previous opera "Gilgamesh", makes everything sound distant at times. It's all audible, but there are balance problems. Also, the English translation of the libretto plays very loose with the Danish original for the sake of maintaining some rhymes and metres, and as the translator was not a native speaker of English it often sounds very weird. The disc is filled out with the percussion concerto "For a Change" (1983). This keeps more or less intact the solo line from "I Ching" for percussion written the same year (best heard on a BIS disc), but orchestrates it in a way that makes its inspiration by Adolf Wolfli all the more evident; imagine "I Ching" crossed with the Symphony No. 4. The percussion part here is a tour de force, but I find I prefer the solo work more than the orchestration. "I Ching" continues to be performed by every new generation of percussionists, while this concerto has fallen into obscurity, so I guess I'm not alone. And certainly the world premiere recording of "I Ching" on a BIS disc has much better sound than this obviously live recording." |

Track Listings (18) - Disc #1

Track Listings (18) - Disc #1