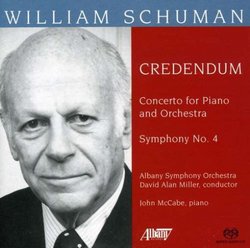

| All Artists: William Schuman, David Alan Miller, Albany Symphony Orchestra, John McCabe Title: Schuman, William: Credendum, Piano Concerto, Fourth Symphony Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 0 Label: Albany Records Original Release Date: 1/1/2003 Re-Release Date: 3/25/2003 Album Type: Hybrid SACD - DSD Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Instruments, Keyboard, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 034061056621 |

Search - William Schuman, David Alan Miller, Albany Symphony Orchestra :: Schuman, William: Credendum, Piano Concerto, Fourth Symphony

| William Schuman, David Alan Miller, Albany Symphony Orchestra Schuman, William: Credendum, Piano Concerto, Fourth Symphony Genre: Classical |

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsFine new recordings of three important Schuman pieces J Scott Morrison | Middlebury VT, USA | 04/13/2003 (5 out of 5 stars) "This release contains three of William Schuman's important pieces from the 1940s: "Credendum," the Piano Concerto, and the Fourth Symphony. All have a toehold in the repertoire (and indeed I've heard all three of them in concert) but, with the exception of "Credendum," they have never had decent recordings. This release featuring the Albany Symphony Orchestra under David Alan Miller, and with the distinguished pianist and composer, John McCabe, fills that need. "Credendum," (Latin for "That Which Must Be Believed," and subtitled "Article of Faith") exists in this orchestral version and also in a wind band version fashioned by the composer. It was commissioned by the State Department to honor UNESCO. It has three sections. The first, "Declaration," is a forthright and declamatory movement primarily for brass, winds and percussion. It feels like an oration about important things. The second section, "Chorale," is primarily for strings and is an urban nocturne. It is interrupted by the bustling "Finale," which eventually leads back to a restatement of the striking "Declaration" material. This piece has always struck me as the most rhetorical of Schuman's works and, given the circumstances of its commission, that is appropriate. There is still available a recording of "Credendum" by Eugene Ormandy conducting the Philadephia Orchestra; the current performance is its equal and is in superior sound. I have a soft spot in my heart for the Piano Concerto (1943). I was attending a public rehearsal of the piece many years ago (Samuel Lipman was the pianist) and noticed a woman in the audience following a score. I asked if I could look on, and thus started one of my longest and closest friendships. The piece is brashly jazzy in spots, and features one of Schuman's most characteristic techniques, that of rhythmically interesting modern counterpoint. Schuman was certainly one of the most skilful of mid-century America's contrapuntists. The fugal sections of the finale are light-hearted and invigorating. Particularly effective is the middle movement, an achingly yearning night-piece, reminding one of the better-known "Lonely Town" that Leonard Bernstein wrote a year or so later for his ballet "On the Town."The Fourth Symphony (1941) is similar to its more famous brother, the Third. It is in three movements. It begins with a mournful English horn solo accompanied by a solo bass viol; this sets the tone for the symphony as a whole. It is dark, passionate, often bitter in tone. (That tone was perhaps appropriate in that its première came only weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor.) The last movement features an attractive fugue - Schuman seems to work fugal passages into most of his orchestral music - which is heard above the opening movement's striding bass line; eventually the two themes are set against each other in the bass voices before the symphony comes to a close in a blaze of victorious C major. Schuman's music now strikes a somewhat nostalgic chord in that it celebrates the broad-shouldered, if occasionally bewildered, optimism of the industrial, urban USA at a time when that optimism was being tested by the Second World War. The big rhetorical gestures may now feel a little trite; the irony of our age doesn't allow for that kind of open-hearted determination, more's the pity. It is strong, attractive, skilfully made music that undoubtedly will last, even if it is somewhat out of fashion these days.David Alan Miller obtains lively, lovely performances from the Albany Symphony Orchestra, a group that for decades has made a real reputation for itself by playing modern American music. John McCabe gives an alert and musical account of the piano concerto, certainly outdoing the old and inadequate recording with Gary Steigerwalt and the MIT Symphony. And the performance of the Fourth Symphony easily outshines the old and now-unobtainable recording by Robert Whitney and the Louisville Symphony.Scott Morrison" Transfigured Bill David Thierry | Chicago, IL United States | 03/27/2010 (4 out of 5 stars) "If you don't like contrapuntal writing you're just not going to like William Schuman's music. If you are a fan like moi you'll enjoy these three pieces. If you are a fan you know how much Schuman loved to write for Brass and the first work is a terrific piece for brass ensemble. It's not a hard sell. The piano concerto I need to invest more time in as there is more here than meets the ear, a modern American Bach. I wonder who his influences are here. The piano writing has the clarity we expect from Bach and Mozart, even Stravinsky but it's all Bill Schuman's own when all is said and done. His third symphony may not be an Eroica but it's a very hard act to follow and I think he just COMPOSED. The fourth symphony is immediately different from the third and while not as immediately lustrous with appeal, it's William Schuman, as dependable a product as a Cadillac in it's glory days. His writing for strings was very distinct. You recognize the Schuman signature. His writing for brass was pretty much as glorious as Sibelius or Mahler but very much his own. If only someone would rerelease his string quartets and there was a curious piece he wrote, I believe for viola, chorus and orchestra I'd like to study again. He even did an opera of Casey at the Bat that I unfortunately missed. I think of him as personifying a kind of American Classicism, Emerson, Thoreau, whatever that might mean and ultimately something noble in the music that one rarely hears except in Beethoven's string quartets particularly, nobility."

|