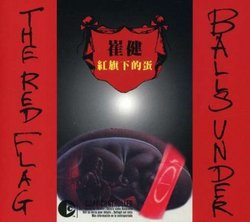

| All Artists: Cui Jian Title: Balls Under the Red Flag Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 0 Label: EMI Release Date: 8/20/2007 Album Type: Import Genres: International Music, Pop, Rock Style: Far East & Asia Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 094634650328, 094634650359 |

Search - Cui Jian :: Balls Under the Red Flag

| Cui Jian Balls Under the Red Flag Genres: International Music, Pop, Rock

|

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSimilar CDs |

CD ReviewsLao Cui's rough-on-yer-ears, street-smart masterpiece Greenlight | Vermont | 08/03/2008 (5 out of 5 stars) "As you already know, Cui Jian became the soundtrack of the 1989 Beijing spring. Cui, a former coronet player with the Beijing Philharmonic who took up guitar, gained public appeal by penning hard-hitting songs with a light melodicism that went down easy with young Chinese hungry for Taiwanese and Canto-pop. But in the years after Tiananmen, Cui bore as much of the clampdown as anyone, with a ban on any public performance, and coming under constant surveillance. In a few more years he'd had enough. (As he grumbles on this album's title track, 'Chi BAO le... Chi BAO le....') In 1994, 'Balls under the Red Flag' was the result.

For any prospective listeners who were sorely disappointed not to hear the punk you expected on buying the 1986-1996 Cui Jian collection, it may be helpful to know that the collection omits a number of controversial songs, and only samples two tracks from this wrenching 1994 session. If you already 'get' White Light/White Heat-era Velvet Underground, or Sonic Youth (circa Sister or Daydream Nation), or Conference of the Birds-era Dewey Redman, then this album will be a familiar soundscape -- it's pure, unadulterated kinetics. And if half of those reference points are meaningless to you, you may want to check more of them out before you try this one out on your ears. Do yourself an important favor too by bypassing track #2, the album's only weak one, a rambling tune that wound up too dirge-like. (Another reason to be disappointed in the Best Of, which samples that tune.) Hong Qi xia de Dan is gutbucket improv at its most abrasive, sarcastic, defiant, and jubilant. Cui Jian's vocals were hoarse and grating even at his debut in the '80s, but here he channels the five years of post-Tiananmen clampdown with all the barb and venom of The Dead Kennedies' Jello Biafra. Sometimes the whole band is moshing like madmen. Sometimes they're out to break new (and ancient) ground -- by proving that 'traditional instruments' like the suona and zheng offer the kind of punk and free jazz cred that the Chinese scene needs. (Jazz aficionados take note: Dewey Redman often played the Chinese suona on his albums, calling it the musette.) In other tunes, the band is jamming as a unit, inspired by saxophonist Liu Yuar, who was already holding court like this late into the night in unadvertised sessions at Beijing's CD Jazz Cafe. (See-dy (nudge nudge) get it?) This album is also a lot like how it sounded to hear Lao Cui live in this underground period, at one-set, word-of-mouth concerts in new venues like the Sunflower Club. When the unspoken ban on televised broadcasts of Cui Jian's music finally lifted in 2000, the first song he chose to sing was the opening cut off this album: "Fei le" (Flown, or Flying). The initial bars of the album are an errant, dissonant Roman candle of a guitar. Then the rhythm morphs adroitly into a coaxing, soul-coal chug. It's punctuated with gunshot-like go-go percussion, wild bari sax soloing, Chinese crash cymbals, and the cool fury of a growled Public Enemy rap. Track three bashes away at the Chinese music scene like Paul Simonon dismantling his bass on the cover of The Clash's London Calling. Liu Yuar's soloing throws in everything but the kitchen sink (an off-kilter Beethoven's Fifth, some cookoo-clock chimes), while lead guitarist Eddie Randriamampionona, an emigre from Madagascar, can be heard on the sly to draw-and-quarter an unduly-famous tune by The Carpenters. (Insensibly, the first Western megastar of the Chinese pop scene was none other than Karen Carpenter.) Both tracks are after a new sound, and are as intense and original as anything written by the great British and American punk acts. There is so much more here than just those two songs. Again, the only weak track is #2, and every other boils over both with heartbreak and quiet pride. Beijing Gushi (Beijing Story), track #4, the most poignant, ambles into view with the sounds of a crisp Beijing spring morning. Alongside an acoustic groove, it kicks off with some whispered vocals, jazzy flute, alto sax and dizi. The song leads up to a beautiful Prince-inspired falsetto bridge that might just be a pedestrian part of the narrative on the surface, but comes so unexpectedly that it's more like a moment of eavesdropping on an unnamed, intensely private struggle. With its slow jam up and over that bridge, it's played in a spirit of muted liberation -- reminiscent of a New Orleans-style wake, for an early-90s Beijing social scene whose spark was basically snuffed out, or at best only barely aflame. How has it taken 14 years for the first review of this great album to show up on (non-Joyo) Amazon? In general, the Beijing scene took a different turn in the 1990s, away from the clear-eyed punk-jazz manifesto of this 1994 album. The sound that caught fire on Hong Qi xia de Dan was greeted with total confusion by Chinese youth, who were either too young to have been a part of the '89 scene, or if old enough, almost universally unfamiliar with the new, more challenging musical references Lao Cui drew on here. It didn't help that the album remained banned on the radio (with very rare exceptions that I ever heard). All of this meant that, while Cui Jian's career has gone through a revival in this more freewheeling decade, the band's independent and very cosmopolitan sound tends to be lost on young Chinese listeners. Unfortunately, many Western listeners have also come to Cui Jian's albums seeking something instantly accessible, and tend to have a diametrically opposite reaction; the 1989-era anthems sound quite dated by today's production standards, and new listeners just don't hear what all the hype over Lao Cui was about in the first place. But you may no longer need convincing: Hong Qi xia de Dan repays repeated, even repetitive listens. And if you do need convincing, know that on Side B the tunes stand up just as tall -- that rare B-side that's every bit as sharp, exhilirating and full of surprises as the first. Stick with other artists if you're after karaoke- or turntable-ready tracks. If you want to understand how Western alternative, jazz and hip-hop music impacted the Mainland scene, Hong Qi xia de Dan is the right place to start. It'll be a while yet 'til younger Chinese musicians reconnect the dots here, as it may take another decade before the Mainland music scene becomes familiar with the full range of Western musicians referenced here by Lao Cui and the band. Lao Cui's 'forgotten' Hong Qi xia de Dan was miles ahead of the competition in the Chinese underground at the time, and still sounds raw and confident today. It leaves no doubt about its legacy. Sooner than they suspect, musicians, critics and historians will be taking a longer look back, and embracing this 1994 album as a major pop culture landmark." |

Track Listings (8) - Disc #1

Track Listings (8) - Disc #1