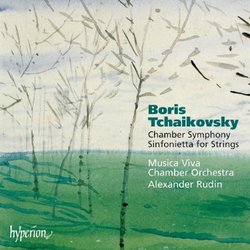

| All Artists: Boris Tchaikovsky, Alexander Rudin, Musica Viva Chamber Orchestra, Ludmila Golub Title: Boris Tchaikovsky: Chamber Symphony; Sinfonietta for Strings Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Hyperion UK Release Date: 7/13/2004 Album Type: Import Genre: Classical Style: Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 034571174136, 003457117413 |

Search - Boris Tchaikovsky, Alexander Rudin, Musica Viva Chamber Orchestra :: Boris Tchaikovsky: Chamber Symphony; Sinfonietta for Strings

| Boris Tchaikovsky, Alexander Rudin, Musica Viva Chamber Orchestra Boris Tchaikovsky: Chamber Symphony; Sinfonietta for Strings Genre: Classical |

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsFine touches of Imagination from a very enterprising persona David A. Hollingsworth | Washington, DC USA | 07/21/2004 (5 out of 5 stars) "My interest of and admiration for Boris Alexandrovich Tchaikovsky (1925-1996) had truly blossomed over the years. My first acquaintance with his music was made with his Second Symphony (1967). Reissued by Russian Disc from the original Melodiya, it's the Symphony that struck me (even to this day) as a piece of considerable originality and keen structuralness (and how ingeniously was he in quoting briefly Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, and Schumann towards the end of the first movement without doing an injustice to its structural coherence). Upon hearing the Symphony, I've took notice of how his melodic language did, at least to some extent, belie both the conservative and the avant garde tendencies of that period; the latter tendencies that Schnitttke, Denisov, Tishchenko, Knipper, et al. championed relentlessly.

Yet Boris Tchaikovsky absorbed the traditionalism of his teachers Myaskovsky, Shostakovich, and Shebalin, while remaining refreshingly enterprising. Anyone who is familiar with his Partita for Harpsichord, Cello, Piano, Percussion, and Electric Guitar (1965), for example, can attest to his yearning to try new things, to vary his expressionistic devices while maintaining his idiom within the principle of accessibility. The additional recordings I?ve acquired later, thanks in part to the Boris Tchaikovsky Society, confirm my belief that this composer ought to be much better known. He's a reminder of how to mold music in various ways that are progressive, yet not necessarily to radicalize music according to the anti-nomenklatura norms of the 1960s and beyond. Only his later works like the Sextet for Winds and Harp (1990) and Symphony with Harp (1993) did Tchaikovsky looked back with some nostalgia. But his formula remained his, and artists like Kondrashin, Fedoseyev, Barshai, Rostropovich, and Emilia Moskvitina showed some real feel, appreciation, and advocacy of his true talent. Thus, ample credit and gratitude shall be given to the Boris Tchaikovsky Society as well, whose tireless efforts in bringing his music to the fore of recognition and appreciation give the composer his honor he richly deserves. Likewise, the Hyperion label and all involved must be gratefully acknowledge for their courage, intuition, and sheer enterprise. Having been blowned away by his masterpiece, the Trio for Piano, Violin, and Cello (1953) and his Capriccio on English Themes (1954), I found myself very warmed to his Sinfonietta for Strings. Likewise composed in 1953, this work brings about a more subtle side of the composer. As in his Trio, the Sinfonietta is very traditional structurally, therefore a rather atypical Soviet musical product (as David Fanning aptly points out in his booklet essay). It's a very novel piece, and while his musical identity was not fully formed shortly after his fairly formative years, there's some idiomatic touches throughout. The Sonatina movement have a Parisienne feel to it; its also a tad witty Shostakovich would have approved (even would Myaskovsky for that matter). But the middle movements brings to mind Piotr Illyich Tchaikovsky, particularly the Waltz (yet even here, my mind rested briefly on Myaskovsky). Yet one cannot simply call them derivations, for the modernity Tchaikovsky espouses brings about its own individuality. The slow movement is a good case in point, reflective and beguiling, yet a striking foretaste to his styles of his later years. The Rondo is an appealing close; its more satirical than the Sonatina and has that refreshingly Mozartian neoclassical eloquence. Tchaikovsky's Chamber Symphony (1967), written three years after his Cello Concerto is quite reflective also, not as extroverted as the Concerto, but serene in character. The Sonata first movement is a fine example of this as is the Chorale Music (third movement). It's a movement longing in nature and Rudin and his Musica Viva Chamber Orchestra brings out its melancholy with quiet poise and compelling concentration and verve. The effective harpsichord writing in this movement becomes more so in the next, where the mood is more outgoing (with Tchaikovsky fond of his neoclassical leanings). The March Motifs is rhetorically very Boris Tchaikovskian. Evoking the first movement of his Second Symphony, also written in 1967, this movement enjoys a more sustained musical development. The Serenade is Bachian is in a sense, and while its reflective qualities serve as a closure to this piece, it may be quite as contemplative as well, as though Tchaikovsky have more to say. The Six Etudes for Organ and Strings (1976) begins strikingly on a serious yet on a muted note (the organ comes up decisively here). And while the Allegro non troppo is more lively, its ends on a fairly grim note. But majesty pervades in the Moderato con moto, only to become climactic @ 2'36". The fifth study is, as Fanning points out, a 'failed toccata' thanks to the organ. I confessed having laughed to this movement at first, partially because its sounds comical yet defiantly mocking (organist Ludmila Golub is rewardingly satirical here). But the final two studies are dignified in their own rights (the fifth is especially memorable and cogitating and I love the way the sixth etude closes this work). The Prelude "The Bells" (realistically yet imaginatively orchestrated by Pyotr Klimov) as composed in 1996, and as I've alluded before, the sense of nostalgia remained with Tchaikovsky in the remaining years of his life. It's an alluring miniature, and an elegant ending point to one of Russia's most creative persona. While I'll hold firm my Melodiya recordings of these works, this Hyperion disc is a very warm welcome. Alexander Rudin paced the works admirably and the Musica Viva Chamber Orchestra responds with flair and elegance (though the strings are not as illuminating and nourished as those of Fedoseyev's reverberant USSR Radio & TV Symphony). Moreover, I lean more towards the great maestro's way with the Sinfonietta; he adds a bit more of a touch of sentimentality and poetry in the middle movements that takes the piece above its naivete. Nevertheless, a great disc and a promising start in a rediscovery phase of Boris Tchaikovsky?s musical art. More installments please. " |