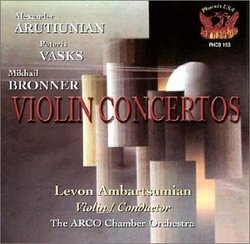

| All Artists: Alexander Arutiunian, Peteris Vasks, Mikhail Bronner, Levon Ambartsumian, Lewis Nielson, ARCO Chamber Orchestra Title: Violin Concertos of Arutiunian, Vasks, Bronner Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 0 Label: Phoenix USA Original Release Date: 9/1/2002 Release Date: 9/1/2002 Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830) Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 094629301532, 009462930153 |

Search - Alexander Arutiunian, Peteris Vasks, Mikhail Bronner :: Violin Concertos of Arutiunian, Vasks, Bronner

| Alexander Arutiunian, Peteris Vasks, Mikhail Bronner Violin Concertos of Arutiunian, Vasks, Bronner Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsNot too demanding, between neo-tonal/neo-romantic and world Discophage | France | 03/31/2010 (3 out of 5 stars) "All three Violin Concertos featured here share some distinctive features: all three were written by composers from the ex-Soviet area, two of them from the outskirts of the empire (Alexander Arutiunian, born in 1920, is Armenian and Peteris Vasks, born in 1946, Latvian) and one dead center Russian; all three composers received their formal training in the Soviet system - Arutiunian in Yerevan then Moscow in the 1940s, Vasks in Vilnius in the 1970s (the neighbouring Lithuania - he'd been banned from studying in his home Latvia because of his father's religious activities), Mikhail Bronner in Moscow in the late 1970s. The three concertos are written for string orchestra, and all three partake of the return to tonality and neo-romanticism that marked (more as a consequence or symptom than as a cause) the demise of both the all-triumphant serial avant-garde and the Soviet Union - and dare I say there might be a link between both? Granted, the Communist regime more or less officially rejected serialism, considered as bourgeois formalist decadence; still, both shared the belief that history was subjected to iron laws, that there was a certain necessary and linear development (of technical, social and economic History in general, of music in particular) that the avant-garde (of the Proletariat and of composition), enlightened by the teachings of Marx-Lenin and of Webern-Messiaen, was aware of and whose historical role it was to bring into being: away from the hieararchies of tonality through the strict disciplines of serial combinations, into the abolition of classes via the dictatorship of the Proletariat. Well - History showed the vanity of those beliefs (in music I mean; in general history, just wait - no, just kidding). OK, that was my minute of cheap sociology, it's like my jogging (usually simultaneous), once a month, no more, don't exhaust the old machine, just to keep the illusion that I am able to reflect on the broader aspect of things. Thanks for bearing with me, now to the petty issues of music:

The liner notes claim that the composition style of Arutinunian, "formed during the late 1940s, was greatly influenced by vitalist trends prevelant in postwar Soviet art". I don't know what "vitalism" in late Stalin-era Sovet art was (wanna bet they opposed it to "formalism"?) but his 1988 Concerto for Violin and Strings is, in its first movement, wistful and lyrical in a way that may vaguely evoke the Concerto written by Britten fifty years before (but without all those inimitable twists of melody and orchestration that make Britten so unique), or maybe Barber's, and certainly the slow movement of Khachaturian's (but without the latter's unique colors and drama). The finale starts with the same orchestral motto as the first movement, which then develops into more agitated figurations on the violin, in a sunny mood which evokes Rodrigo, really. The second movement starts like a sardonic folk-inspired, Shostakovich-like dance piece and drifts at times into a Bach imitation. There's something of Bach's Air in G arranged by Villa Lobos in the slow movement as well - and, of course, Khachaturian looms large throughout. This is pleasurable, undemanding and quickly forgettable music. It is for Peteris Vasks really that I bought this CD (the cheap price I paid for it helped, of course); I had enjoyed his second String Quartet "Summer Songs", recently heard and reviewed (Vasks: String Quartet No.2/Tüür: String Quartet/Pärt: Fratres for String Quartet). The long (28-minutes) one-movement Concerto "Distant Light" is much in the same vein: it starts with a typical Vasks trick but a highly colorful one: high-pitched violin melismas and trills playing on harmonics, over a hushed punctuations of strings. Very beautiful. What develops from there is simple, plangent to dance-like, highly lyrical (and sometimes close to corny in its hackneyed gestures and heart-on-sleeve outpouring), often hauntingly atmospheric, and at times very beautiful, in an undemanding way (at least to minds trained to marxism - I'm sorry, ears trained to 20th Century avant-guarde music). There's an awesome cadenza at 18:53, leading into a terrifying outburst of almost unbearable agitation, before the return of the plangent and mournful mood of the beginning. Mikhail Bronner's Concerto "Heaven's Gates" (2001) is also in one movement, and is another one of these Big Romantic Things, a cross-breed of Barber (or even Delius), film music and at times the kind of World Music championed by ensembles such as the Kronos Quartet or the Balanescu Quartet, often sweet and even dangerously verging on the saccharine at times, but offering enough fine touches of orchestration and color (especially in the World music parts - but some of those Romantic outbursts are pretty catching too) to keep the interest awake. Levon Ambartsumian - another Armenian and product of the Soviet music education system (Kogan was one of his teachers at the Moscow Conservatory) and another symbol of its demise (he is now professor of violin at the Universtity of Georgia School of Music - in Athens, Georgia, USA, that is) - plays with fine and arresting tone. The liner notes give general introductions to the composers (but not even Vasks' and Bronner's birth dates) but, frustratingly, they manage to be entirely silent about the Concertos of Vasks and Bronner - not even mentioning them. TT 72 minutes. Utlimately, if I keep this disc, it'll be only for the Vasks Concerto." |

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1