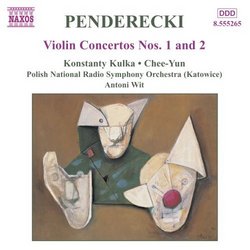

| All Artists: Penderecki, Chee-Yun, Wit, Polish Nat'l Rso Title: Penderecki: Orchestral Works, Vol. 4 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Naxos Release Date: 3/18/2003 Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Concertos, Instruments, Strings, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 747313526529, 747313526529 |

Search - Penderecki, Chee-Yun, Wit :: Penderecki: Orchestral Works, Vol. 4

CD Details |

CD ReviewsNeo-Romantic Penderecki, gloriously played and recorded J Scott Morrison | Middlebury VT, USA | 04/26/2003 (5 out of 5 stars) "I think I've been reading too much 19th-century music criticism lately. Back then the height of music commentary was to write a descriptive program to go with the music - you know, Liszt saying that the slow movement of Beethoven's Fourth Piano Concerto was Orpheus taming the Furies, or Schumann calling the Fourth Symphony a Norse giant between two slender Greek maidens. But when I listened to these two violin concerti by Krzysztof Penderecki (b.1933) my imagination went wild, supplying pictures and scenario, and I was never able to get rid of them. So now, you lucky folks, I'll share them with you. [Read no further if, like me, you don't ordinarily go for this sort of thing.]The First, a one movement mammoth, begins with a solemn introduction in the low strings and timpani, setting the stage for the Pastor (the solo violin) to mount the lectern and begin his sermon. Picture Orson Welles as Father Mapple in the movie of 'Moby Dick.' His tone is now declamatory, then haranguing, now imploring, then minatory. Sometimes his rhetoric is so intense that he speaks in long unaccompanied cadenzas that are as virtuosic as they are impassioned. Sometimes he almost loses control of himself in his desire to convey his message, and sparks fly. Ultimately he flings out a Cassandra-like warning before he, exhausted, lapses into silence. Konstanty Kulka, the violinist in the first concerto, is a middle-aged Polish violinist whose playing reminds me of David Oistrakh. He has a big, burnished tone with an intense vibrato which he uses here in the service of a larger-than-life performance, perfect for the rhetoric of this larger-than-life concerto. The piece itself often reminds me, in tone but not in construction, of the Passacaglia movement from Shostakovich's First Violin Concerto, but expanded to an almost 40-minute length. Imagine that degree of passion for that length of time! Kulka pulls it off. I have not heard the recording by Isaac Stern, the concerto's dedicatee, but knowing his playing I'd assume it is wonderful; I think it is still available.The second concerto, subtitled 'Metamorphosen' and also in one large movement, is an altogether different animal. Written in 1994-95, twenty years after Penderecki wrote the First Concerto, it is an introspective work. If the First is an Oration or a Sermon, the Second is a Soliloquy. This set of variations (structurally it is just that) conjure up the inner struggle of a young man caught up in a tragedy of passion (picture Anthony Perkins as Hippolytus to Melina Mercouri's Phaedra; the step-son having an affair with the step-mother that each is powerless to break off and which ultimately ends in tragedy). Hippolytus (the violin soloist) moons, yearns, becomes agitated with inner conflict, tries to break away, struggles (a masterful fugal passage), and ultimately gives in and is destroyed, sadly, quietly, resignedly. The violinist here is the young American-trained Korean, Chee-Yun, whose tone is slenderer, silvery, more fine-grained than Kulka's, but still intense and passionate when necessary. There can be an inward, almost improvisatory quality to her playing that fits this soliloquy nicely. Again, I have not heard the recording of the Second Concerto's dedicatee, Anne-Sophie Mutter, but can only imagine that it, too, is quite fine. Antoni Wit, conducting the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra (Katowice), provides solid, musical, flexible support for the two soloists, and during the fairly rare orchestral passages - the soloists are front-and-center throughout most of these concerti - reveals an ability to shape the material dramatically. I was especially struck by the opening tutti of the First Concerto: it unequivocally sets the stage for the Sermon to come by signalling 'this is important - pay attention!'Once again Naxos has given us really special performances of important music in warm and refulgent sound, and at bargain prices. Whatta deal!Scott Morrison"

|