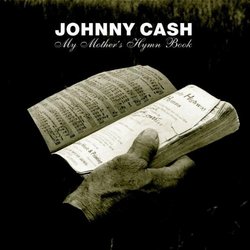

| All Artists: Johnny Cash Title: My Mother's Hymn Book Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 1 Label: Lost Highway Release Date: 4/6/2004 Genres: Country, Pop, Christian & Gospel Styles: Vocal Pop, Southern, Country & Bluegrass Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPCs: 602498613337, 602498625149 |

Search - Johnny Cash :: My Mother's Hymn Book

| Johnny Cash My Mother's Hymn Book Genres: Country, Pop, Christian & Gospel

![header=[] body=[This CD is available to be requested as disc only.]](/images/attributes/disc.png?v=430e6b0a) ![header=[] body=[This CD is unavailable to be requested with the disc and back insert at this time.]](/images/attributes/greyed_disc_back.png?v=430e6b0a) ![header=[] body=[This CD is unavailable to be requested with the disc and front insert at this time.]](/images/attributes/greyed_disc_front.png?v=430e6b0a) ![header=[] body=[This CD is unavailable to be requested with the disc, front and back inserts at this time.]](/images/attributes/greyed_disc_front_back.png?v=430e6b0a) |

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSimilar CDs

Similarly Requested CDs

|

Member CD ReviewsReviewed on 3/6/2012... Great album, wonderful renditions of timeless music.

CD ReviewsPrayers from a Faithful Son and a True Artist Juan Mobili | Valley Cottage, NY USA | 04/16/2004 (5 out of 5 stars) "It is important to say -call it the result of not being warned time after time, of the actual source of posthumous releases- that "My Mother's Hymn Book" is, without exceptions, the exact same collection that appeared as volume 4 of the "Unearthed" set. That said, and for people who can't or would not buy the 5-CD set, this is a remarkable album in its own right. Whether you grew up listening to these or similar songs at home or church or not, whether you are even religiously inclined toward the Christian faith or you profess some form of agnostic alergy to spiritual music, it would be very hard not to be drawn to the austere honesty and profound depth of these renditions. For Cash's devotees, this is yet another true gem from the inexhaustible soul of a great artist. The fact that Cash decided to record these old hymns knowing full well that he was dying makes the listening experience even more meaningful, an act of faith and an artistic document of moving depth, but, and this must be stressed, its musical value is unimpeachable, it is not "great" because of biographical circumstances -imminent death, a last musical statement of glorious and long career, etc.- its greatness is fully attained in artistic value alone. Even at the end, his voice clearlyn weakened by illness, Cash' singing has not lost any of its presence nor the well-earned authority of his phrasing. To listen to Cash, always, is to listen seriously to a man who would never indulge in words he did not mean. Being a proud owner of the "Unearthed" set (you can see my review of the 5-disc set too), yet understanding that not everyone may want to invest so much, I'm glad that this album has been released. So, I do not disparage the record company for putting it out as a "stand-alone" item, although I do resent that it was released around Easter, in the wake of Gibson's "Passion of the Christ", to benefit commercially from such media-fueled controversy. I doubt Johnny would have appreciated such Philistene strategy, yet in the end, as with any authentic works of art, nothing can stain its message." Just As He Was Snubnosed in Alpha | 05/14/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "

The satirical newspaper, The Onion, once featured the headline: Affluent White Man Enjoys, Causes the Blues. The article reports a self-described "blues nut" who is a senior vice-president of a Chicago-area industry that employs-and grossly underpays-African Americans. At least a part of the humor here pokes fun at the Caucasian blues aficionado who "loves the music" but, of course, has never really participated in the culture from which it has emerged. Your typical Taj Mahal concert these days will be attended by throngs of adoring, Abercrombie&Fitch-wearing, baby-boomer yuppies. Then there is the Wall Street trader who is devoted to the music of, say, Doc Watson or Flatt and Scruggs. Though he would hardly wish to spend time in that flyover territory between New York and L.A. and rub elbows with the unwashed for whom such music is a way of life, he enjoys a good PBS bluegrass special featuring Allison Krauss. There is, of course, nothing particularly wrong with this. Great music tends to transcend the culture that spawns it and command a wider audience. It is possible to enjoy folk music without being one of the folk. There is a similar way of appreciating Johnny Cash's My Mother's Hymn Book. One Sunday a few years ago in a small cabin on his property, Cash sat down alone with his guitar, literally thumbed through his mother's dog-eared old hymn book, and recorded the old country gospel songs that his mother once sang to him-songs that he knew by heart. It would be hard to imagine a simpler production. There is Cash's familiar but lived-in voice accompanied by his signature alternating bass line guitar picking. Though several of the songs indicate that they were "arranged by John R. Cash," they are pure and unadorned, like the faith that they express. There is appeal here for people who have never darkened the door of a church-much less a little clapboard-sided church in rural Arkansas. After all, this is Cash and, as they say, if you don't dig Cash you've got no soul. And then, too, there is the cultural appeal of an endangered bit of Americana. Daniel Dennett, "dangerous Darwinian" that he is, once suggested that Fundamentalist culture is worthy of preservation as a kind of museum piece and that perhaps it would be a good thing to keep a few Baptists around in "cultural zoos" of sorts. If this music is appropriately bracketed and thus demythologized, it may well be circulated even among the unbelieving hip. Were he still with us, it would not be difficult to imagine Cash performing some of this music before an appreciative crowd at this year's Bonnaroo. But listening to the recording and reading the accompanying byline, it is obvious that Cash himself is not keeping the music at arm's length. This is an intensely personal creation: a work of love. This was his "favorite album," the one of which he was the most proud. "That was me," he says. Cash is "singing and playing this music back to his mother," recalling a childhood that, though unhappy in many ways, was steeped in the message and music of the Gospel. Some of the hymns have acquired an additional significance for him, too. "When the Roll is Called Up Yonder" and "In the Sweet By and By" were sung at the funeral of his brother Jack ("my best friend"), who was killed in a horrible sawmill accident when Cash was 12. The family sang, "Let the Lower Lights Be Burning" as they gathered around Cash's coma-stricken father on his deathbed. As Cash describes the scene, "though he had been sound asleep in a coma for days, his lips started moving and he started singing that song along with us." But I suspect that Cash himself would tell you that the deepest significance of this music is its message-a message that sustained him in troubled times. He speaks of his "wilderness years" when "the demons crawled up my back." Seriously addicted to amphetamines and barbiturates, and even attempting suicide, but for the grace of God his might have been yet another tragic tale of one who sold his soul to the devil in exchange for stardom. These "powerful songs," he says, were "my magic to take me through the dark places." A self-described "C-minus Christian," Cash says, "even through the dark times, I always felt like I was bound for the Promised Land, especially singing those songs." One gets the impression that, even as he cultivated his image as "one of the original outlaws," as Willie Nelson once described him, he never quite forgot the One of whom his mother had sung. He may have wandered far from home, but he took the hymnal-the hymns, at least-along with him. Here is a white-haired old sinner who has, I wish to believe, finally reconciled himself to God. Cash says that he finally came to accept "that God thought there was something worth saving." I, too, was steeped in this music growing up and, after many years of its absence, it resurfaces into my life through Cash's voice in a powerful way. This is partly due, I suppose, to the realization that a great deal of time has passed while I wasn't looking. Not only does listening occasion childhood memories that seem impossibly distant in my past, but there is the further reflection that the singer-someone who seemed a permanent fixture in the culture in which I was raised-had nearly reached the end of his life as he recorded these hymns, and has now passed on. And so have most of the people in my own past with whom I associate this music. And so shall I. As a friend has observed, it is particularly moving to hear Cash's aged and weary voice singing of "a place where we'll never grow old." Then, too, there is the reflection that Cash had some good reason for recording these hymns literally out of his mother's old hymnal when he did and as he did. Perhaps this is my own interpolation, but it is easy to hear these recordings as outward evidence of a final act of repentance after a life lived as an outlaw on the lam. Hearing Cash sing the words, "Ye who are weary, come home," it is equally easy to think that he has finally accepted that very offer. And, in light of such thoughts, I realize that it is only as a participant in the culture of belief that this music can be fully appreciated. Hearing an aged and experienced Cash singing that his only plea is Christ's blood and Christ's invitation, I realize that I stand in need of such grace just as surely as does this outlaw and former drug addict. And I recognize that I, too, wrestle with demons. Such reflections complete the circuit between the performer and his audience in a way that is just not available to those who would "bracket" the message of the music and hear it as a cultural artifact. " |

Track Listings (15) - Disc #1

Track Listings (15) - Disc #1