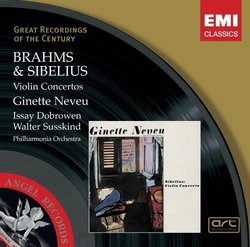

| All Artists: Johannes Brahms, Jean Sibelius, Issay Dobroven, Walter Süsskind, Philharmonia Orchestra of London Title: Brahms, Sibelius: Violin Concertos Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: EMI Classics Original Release Date: 1/1/2003 Re-Release Date: 9/13/2005 Album Type: Original recording remastered Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Instruments, Strings, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 724347683121 |

Search - Johannes Brahms, Jean Sibelius, Issay Dobroven :: Brahms, Sibelius: Violin Concertos

| Johannes Brahms, Jean Sibelius, Issay Dobroven Brahms, Sibelius: Violin Concertos Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSimilar CDs

|

CD ReviewsREMASTERING HELL! AVOID! Milan Simich | 05/11/2007 (1 out of 5 stars) "These great performaces are ruined by a horrible 'remastering' job. This is digital hell, robs every ounce of music, it's like every nore is disconnected from each other! Horrible job. Get the 'cheapo' reissue. The music breathes on that one unlike this garbage!" Ah - reputations... and NOT a Sibelius for the ages Discophage | France | 10/18/2008 (3 out of 5 stars) "Ah - reputations. How are they established? In the case of Ginette Neveu, part of the answer at least is clear enough: through her tragic death, at the age of 30, in the plane crash that also claimed the lives of her brother and accompanist Jean and of middle-weight boxing champion and Edith Piaf lover Marcel Cerdan.

Would she enjoy such a legendary status if it hadn't been for that tragic circumstance? I've heard recently and reviewed another EMI references disc with the Violin Sonatas of Strauss and Debussy, Ravel's Tzigane and Chausson's poem (piano accompaniment): they were nothing special (and even less than that), both musically (excessively languid and long-drawn out Strauss) and technically (obvious strain in Tzigane): Ginette Neveu. Likewise, her live Tzigane with Munch in New York in January 1949 shows that her technique wasn't really up to the piece's demands (Ginette Neveu Historic Broadcast Performances: Beethoven, Chausson, Ravel). Hearing this Tzigane had me even puzzled that Neveu was awarded the first prize at the 1935 Wieniawski competition, ahead of no less than David Oistrakh, especially on the basis of this same Tzigane, and it now gets me wondering if some geo-politics might have been involved in the jury's decision. Or maybe what sounded impressive with a 16-year old isn't so impressive ten years after. Now, I know that such sceptical comments will be ruffling to the Neveu admirer. But I approached these recordings with no hidden agenda, no unfavorable bias - on the contrary, as with any artist of reputation, if anything I had a favorable bias, and likewise with these recordings of Brahms and Sibelius, which even more than the other ones have always enjoyed a legendary status. But then, I listen to the playing, not the reputation. I started with Sibelius and, pace the laudative notes by old recordings expert Tully Potter, it seemed to bear out my scepticism. I won't hold it against Neveu that her tone tends to thin out in the higher reaches, and I'll rather mistrust my own ears for the various spots where her intonation seemed to me to come dangerously close to skidding off track. Am I the only one to hear it? Obviously producer Walter Legge, conductor Walter Süsskind and the engineers in the recording session didn't hear it (or if they did, decided it didn't matter, or they couldn't fix it). But my qualms have more to do with Neveu's musical options. With Sibelius' Concerto as with just about any other piece of music, one observes that tempos, as evidenced by the numerous successive recordings, have tended to broaden in the course of the 20th Century. As an illustration, just compare Heifetz' 14:08 in the first movement of Sibelius in his premiere recording with Beecham from 1935 (Heifetz Plays Strauss (Violin Sonata op. 18), Sibelius (Violin Concerto), Prokofiev (Violin Concerto 2); he's even faster in his 1959 remake with Hendl, Sibelius, Prokofiev, Glazunov: Violin Concertos [Hybrid SACD]), Stern's 14:24 in 1951 with the same Beecham, Early Concerto Recordings, Vol. 2 (and 14:08 in his 1969 remake with Ormandy, Tchaikovsky, Sibelius: Violin Concertos), to Sergei Khachatryan's 16:17 and Hilary Hahn's 17:10 (two recent recordings that came my way, Khachaturian, Sibelius: Violin Concertos and Schoenberg Violin Concerto Op.36/Sibelius Violin Concerto Op.47). I'd been wondering when the change took place. Well, it all starts here, with Neveu, in 1945: 16:05. Not that it doesn't work musically: the introduction acquires a gentle, mellow and almost plaintive quality, and the option is quite valid in its own terms; furthermore, Neveu is also capable of muscle and fire, although there are passages of excessive fussiness (for instance the way she insists on the first beat of the arpeggios at 2:22) or lingering (in the cadenza), and Susskind bravely compensates the relative lack of momentum with a barbirollian power and weight. But one only needs to go back to Stern and Heifetz to realize that, while the approach does gain a sense of solemn grandeur and of broad lyricism, it looses the urgency, the forward drive and the searing lyrical intensity. Neveu's coda, at 14:45, is pedestrian where it should be fiery and no-holds barred. On the other hand the slow movement, taken again at an ample tempo, is fine and as beautiful as anyone's. But the finale? Again, here are hard facts: Heifetz took it in 6:44 the first time with Beecham, 6:38 in the stereo remake with Hendl. Stern in 1952: 7:02. Hahn takes it in 7:10 and the modern versions take it anywhere between 7 and 7:30. Neveu? 8:04. If the concerto's finale, with its characteristic rhythm, is a gallop, the impression you get with Neveu is that of a trudging canter. The approach does pay at least a few dividends: unlike all the other recordings I can remember except Hahn (and including Heifetz), with Neveu, at such a pedestrian tempo, you don't get (too much) the impression that she is hanging by the skin of her teeth just to keep up with the orchestra. Also, with Susskind's Barbirollian weight and power, you do get some sense of something inexorable and epic, and you can fancy that the Nordic Gods rode such sturdy draft horses (or were they reindeers?) rather than Arabian stallions. And at least, Neveu's approach to tempo has the merit of consistency throughout the three movements. Still, the lack of bite and drive in the finale sends me dozing off. No such reservations with Brahms, fortunately. Recorded a year after Sibelius, it is a fine version, taken again at quite spacious tempos, enhancing the work's broad lyricism, but again Neveu is capable of muscularity and drive. The finale may not have the joyous vivacity of Heifetz, but then it is notated "Allegro giocoso, MA NON TROPPO vivace". Is it a version of legendrary stature? Hard to say, there have been so many legendary versions of that work throughout the history of recording. Neveu's is one good one among many good ones. I don't have other transfers to compare these to, but I hear nothing in them as exceptionable as one other reviewer makes it, and I don't think my appreciation of these versions' interpretive merits would significantly change with a better transfer. " |

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1