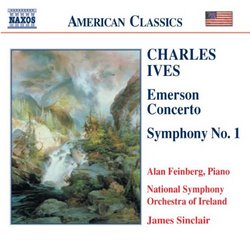

| All Artists: Charles Ives, James Sinclair, National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland, Alan Feinberg Title: Charles Ives: Emerson Concerto; Symphony No. 1 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Naxos American Original Release Date: 1/1/2003 Re-Release Date: 10/21/2003 Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Concertos, Historical Periods, Modern, 20th, & 21st Century, Instruments, Keyboard, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 636943917527 |

Search - Charles Ives, James Sinclair, National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland :: Charles Ives: Emerson Concerto; Symphony No. 1

| Charles Ives, James Sinclair, National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland Charles Ives: Emerson Concerto; Symphony No. 1 Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsCharlie Done Right. Part III. Bob Zeidler | Charlton, MA United States | 10/31/2003 (5 out of 5 stars) "Superficially, this new Naxos release of Ives's 1st Symphony and the premiere recording of his Emerson Concerto resembles an earlier Naxos release of his 2nd Symphony and Robert Browning Overture (a review of which I gave the sobriquet "Charlie done right"). The resemblance is in the pairing of an "accessible" Ives work with one more "knotty." In each case, the symphony receives a performance using a new critical edition (by Jonathan Elkus in that earlier release and by James Sinclair in this one). And each critical edition affords a fresh view of such "accessible" Ives. But the similarities shouldn't be overdrawn; while the Robert Browning Overture is knotty under the best of circumstances, the Emerson Concerto turns out to be more accessible than I expected; a pleasant revelation.

The 1st Symphony was a "student" work, Ives's Yale thesis work written for his teacher, Horatio Parker, but with the clear influence of his "experimentalist" father, George Ives. (An idea of Ives's "experimentation" is found as early as in the first movement, nominally in D minor, where a passage modulates through eight different key signatures. A near-apocryphal anecdote related by Ives in his later years has Parker at least mildly annoyed by Ives's insistence on these modulations, but finally "throwing up his hands" in defeat and stating "But you must promise to end in D minor.") If Ives learned from his father, he also clearly learned from Parker. The work is very much in a late 19th-century European mold, with strong resemblances to both Dvorak's New World Symphony (particularly in the second-movement Adagio molto, an obvious "borrowing" from the famous Largo of the Dvorak) and Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 6 in the final movement. If not of the caliber (and endurance of appeal) of other such "first efforts" in the genre as those by Berlioz, Mahler and Shostakovich (at age 19!), it is nonetheless eminently appealing and, even, entertaining. Moreover, it lacks nothing by way of craft except perhaps for an overabundance of ideas (seemingly so rich that a "thriftier" composer might have stretched another symphony out of them). He demonstrates, in this youthful work, that he is as well a very skilled orchestrator, despite his youth and inexperience. Over the years, I've collected what I think are (or were) all the available recordings of this work: Morton Gould with the Chicago Symphony (the world premiere recording), Eugene Ormandy with the Philadelphia Orchestra, and, most recently, Michael Tilson Thomas with (again) the Chicago Symphony. This new Sinclair performance puts them all out to pasture. (Only the Gould is remembered with fondness, because it was a "discovery" for me.) Sinclair's critical edition restores a first-movement repeat and adds side-drum percussion (more about THAT later) in the Finale, and as well, I expect, corrects numerous small errors. His reading of the work is superb, the National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland turn in a splendid performance, and the sonics are among Naxos's best (which means "very good indeed"). Particularly felicitous is Sinclair's interpretation of the Adagio molto second movement, where he lovingly lingers over its beauties, in which Ives serves notice that he is a true melodist, not merely a "note spinner," when he chooses to be. The coda of the Finale is certainly enhanced by the inclusion of side drums having a very "American" flavor, perhaps the single best hint that this is the work of an American composer despite its European flavor otherwise (as if "you can take the boy out of Danbury but you can't take Danbury out of the boy"). Such percussion scoring would become commonplace a generation or so later; it became a frequent touchstone in the works of William Schuman, as one example. The other work, the Emerson Concerto in its recording premiere, hardly arrives "unannounced," as Alan Feinberg, the soloist here, has performed the work (to splendid reviews) in concerts since its concert premiere in 1998. But for most of us this is a "first hearing." The work is"realized" by David G. Porter, an Ives scholar who must number among the fearless of this small community, from incomplete sketches of an "Emerson Overture" for piano and orchestra (one of four such proposed overtures on literary figures, of which only the Robert Browning Overture saw completion). According to Sinclair's authoritative "Descriptive Catalog of the Music of Charles Ives," the terms "overture" and "concerto" can be used interchangeably. While Ives never completed the work, he did succeed in subsuming many of its themes in the Concord Sonata and the Four Emerson Transcriptions for Piano that are closely related, thematically, to the Concord. By far the most famous of these themes is the four-note "Fate" motive that begins Beethoven's 5th Symphony, a theme for which Ives ascribed greater "universality" than did Beethoven himself. Ivesians coming upon this work for the first time will find it to be a fascinating, and at times compelling, mix of "the old" and "the new and strange." For the most part, connections to the Concord and the Emerson Transcriptions will be recognized, but of course transmogrified. The "Fate" motive seems to be more dominant here than in the keyboard equivalents; it is clearly the unifying theme for all four movements. Feinberg is absolutely heroic in his performance (as he needs to be, needless to say). Orchestrating the work (and here Porter has done a superb job) clarifies far more than it obscures, vis-à-vis the keyboard works. As would be expected, shattering dissonances live side-by-side with passages of transcendent beauty. I was even able to pick out a passage or two where quarter-tones seem to have been employed by Porter; they are for the most part in the quieter passages, and they simply glow with beauty. As much as I've enjoyed the work in its first few hearings, I think it will grow on me even more over time. And the newly-revised 1st Symphony is a winner on all accounts. Needless to say, highy recommended. Bob Zeidler" |

Track Listings (8) - Disc #1

Track Listings (8) - Disc #1