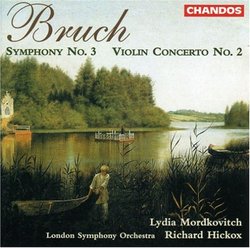

| All Artists: Max Bruch, Richard Hickox, London Symphony Orchestra Title: Bruch: Symphony 3/Violin Concerto 2 Members Wishing: 0 Total Copies: 0 Label: Chandos Release Date: 7/20/1999 Genre: Classical Styles: Forms & Genres, Concertos, Instruments, Strings, Symphonies Number of Discs: 1 SwapaCD Credits: 1 UPC: 095115973820 |

Search - Max Bruch, Richard Hickox, London Symphony Orchestra :: Bruch: Symphony 3/Violin Concerto 2

| Max Bruch, Richard Hickox, London Symphony Orchestra Bruch: Symphony 3/Violin Concerto 2 Genre: Classical

|

Larger Image |

CD Details |

CD ReviewsSome interpretive flaws, but much pleasure is in store with Discophage | France | 02/16/2010 (4 out of 5 stars) "I had pinned some hopes on this recording of Bruch's third Symphony by Richard Hickox.

I realized only recently the many beauties of Bruch's Symphonies. Masur's complete recording, heard in the late 1980s (it was recorded between 1983 and 1988), had failed to leave a strong impression (Bruch: The 3 Symphonies, Swedish Dances (Schwedische Tanze)). The abiding feeling was that I had all heard it before, in Schubert, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms, Bruckner. A chance encounter with the symphonies of Fibich recently raised the question of what it is that makes it the music of a "minor" composer, as opposed to the "major" ones mentioned above (Fibich: Symphony No. 1 in F major, Op. 17; The Tempest, Op.46, Zdenek Fibich: Symphonies Nos. 2 & 3). And the tentative answer was that, as enjoyable as it may be, the music doesn't give you the impression that you haven't heard it before. I decided to test that "hypothesis" on Bruch. I hadn't listened carefully enough twenty years ago. Sure, much in Bruch's Symphonies you have heard in those "major" composers; that makes them hardly forward-looking works in their days (1868, 1870 and 1883-revised in 1886). But then, heard today, such consideration doesn't count for much. One can listen to Bruch's Symphonies for what they offer, not for what they don't. And rehearing them, I must now turn my formula around: they may not give you the impression that you haven't heard it before, but they are highly enjoyable nonetheless. I won't say that Bruch's output is on a same plane with Brahms' (nobody is) or Bruckner (because Bruckner is somewhere else entirely). But I hear in them nothing that makes them inferior to those of Mendelssohn or Schumann - on the contrary. Why do theirs enjoy such popularity, and not his? Maybe because they weren't trendy enough in their days, and fell in oblivion before they had a chance. In fact I've enjoyed Bruch's Symphonies so much that I bought the study scores, recently reissued, after possibly a century of unavailability, by an enterprising German publisher, Musikproduktion Hoeflich, specialized in bringing back to circulation obscure and off-the-beaten track repertoire. Bless them! I also acquired more recordings, including the competing cycle of James Conlon, recorded in 1992-93 (Bruch: Symphonies 1-3, Concerto for 2 Pianos). It turns out that Conlon's fortes are Masur's deficiencies, and the other way around. Conlon has the much better sonics - Masur's East-German recording sounds muffled, the edges are blunted and many details from brass and woodwind are simply lost: frustrating to see it on the page and not hear it (the 3rd fares best, though). On the other hand, interpretively, I find that Masur does much better justice to the scores. His tempos are always closer to Bruch's metronome marks (he wrote very detailed ones in Symphonies 2 & 3). It is not just a question of being faithful to score for the sake of it (although, in such rarely recording works, there is indeed a value to letting you hear it exactly as the composer intended it): Masur's more urgent approach highlights the symphonies' intense passion and romantic turbulence. Conlon has a tendency to play slower, solemnizing and brucknerizing the music so to speak. In the 3rd Symphony's first movement, he also slows down significantly the second, lyrical theme, presumably to "fully press the lyrical juices". But the result is only to check the forward momentum and unduly sentimentalize the music. Masur does exactly what Bruch prescribes: a slight easing of tempo that, with the subsiding dynamics, feels more like an easing of tension than an actual slow down. I refer you to my reviews of both sets for more details. So my hopes with Hickox were to get the best of both worlds, Conlon's sonics at the service of Masur's approach. Not entirely fulfilled. Hickox's approach is similar to Conlon's, but without his excesses. His sonics are better even: everything comes out clearly, but the brass aren't as aggressively spotlighted, sounding more organic and natural. Interpretively, Hickox' finale is great: it has all the sweep and passion of Masur (Conlon is pretty good here as well) with better sound. His first movement introduction is far slower than Bruch indicates (and Masur executes), slower even than Conlon's (quarter note 48 to Conlon's 52 and Bruch's 72); but Hickox must be aware that such tempo is problematic, because he accelerates markedly in the course of the introduction, reaching 80 (as if his quarter note beat had become a half note beat). It is expertly done and sounds organic - but it is not what Bruch wrote! Like Conlon, he slows down significantly the second and lyrical theme at 3:45, sentimentalizing it and somewhat checking the forward motion. But there is plenty of uplifting sweep in the faster sections. Like Conlon, he brucknerizes the 2nd movement, giving it grandeur but making it more stately than it deserves and robbing it of some of its intense passion. The scherzo is fine but doesn't quite have the bubbling energy and zest of Masur at Bruch's tempo. There is nothing likely to chock anybody without a score, and much in Hickox' reading is very good, but having in mind what it might and should sound like, it leaves me a bit frustrated. One originality of the Chandos Bruch Symphony cycle is that each Symphony is paired with one of Bruch's Violin Concertos, as on Bruch: Symphony 3/Violin Concerto 2. Sadly, Richard Hickox died before he could complete the cycle, with 2nd Symphony and first VC left unrecorded. Bruch is still in the mainstream almost exclusively for his 1st Violin Concerto, which has overshadowed all the rest of his output, including his two other VCs. No. 2 op. 44, written in 1877, a year before Brahms', doesn't deserve such neglect. It is full of gorgeous moments and should be standard repertoire. Mordkovitch plays with total involvement and big-boned lyricism, a big tone which can sometimes go gruff, and even strained in the finale, and not always pitch-accuracy in the higher reaches. Mordkovitch and Hickox's broad approach yields grandeur but also a measure of heavy-footedness. Despite these interpretive flaws, this disc will offer many pleasures." |

Track Listings (7) - Disc #1

Track Listings (7) - Disc #1