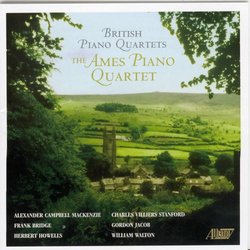

| All Artists: Ames Piano Quartet Title: British Piano Quartets Members Wishing: 1 Total Copies: 0 Label: Albany Records Original Release Date: 1/1/2007 Re-Release Date: 3/1/2007 Genre: Classical Styles: Chamber Music, Historical Periods, Classical (c.1770-1830), Modern, 20th, & 21st Century Number of Discs: 2 SwapaCD Credits: 2 UPC: 034061091028 |

Search - Ames Piano Quartet :: British Piano Quartets

| Ames Piano Quartet British Piano Quartets Genre: Classical

During one of his recital tours to Edinburgh during the 1860s and 1870s, Anton Rubinstein bluntly told Alexander Mackenzie Sie haben keine Komponisten (You [Britain] have no composers). From his account in his engaging mem... more » |

Larger Image |

CD DetailsSynopsis

Product Description During one of his recital tours to Edinburgh during the 1860s and 1870s, Anton Rubinstein bluntly told Alexander Mackenzie Sie haben keine Komponisten (You [Britain] have no composers). From his account in his engaging memoir A Musician s Narrative (1927), Mackenzie apparently let the comment pass unanswered. After all, the Russian virtuoso was simply voicing a view widely heard in continental Europe and even in Britain as well. Many years later, as he surveyed a career that had spanned six decades, Mackenzie noted with many gleams of satisfaction the number of important musicians and composers of high merit who had come along. In company with his slightly younger contemporaries, Hubert Parry, Charles Villiers Stanford and Edward Elgar, Mackenzie was himself part of the generation of musicians born in the mid-19th century who first demonstrated that Britain did have composers and fine ones. Their successors among them Vaughan Williams, Frank Bridge, Herbert Howells and William Walton completed the transformation of European opinion. Along with presenting a compilation of signal British contributions to the piano quartet repertoire, this set offers a sample of the music of some of the very composers who helped deliver British music from its lowly state as a source of jests to a place of international recognition and esteem. Similar CDs

|

CD ReviewsA Stunner! J Scott Morrison | Middlebury VT, USA | 04/23/2007 (5 out of 5 stars) "It is to the credit of the Ames Piano Quartet, a group long-resident at Iowa State University (located in Ames, Iowa, whence the group's name), that they have recorded six -- count 'em, six -- piano quartets by British composers and not a loser among them. This 2CD set contains music by Mackenzie, Bridge, Howells, Stanford, Jacob and Walton. The informative program notes by Karl Gwiasda indicate that it all got started when a British musicologist, John Purser, during a residency at ISU brought their attention to the piano quartet of Alexander Campbell Mackenzie (1847-1935), a work never before recorded. This piece, let me say, is a major discovery. I would, in fact, place it in the exalted company of similar music by Schumann and Mendelssohn. In the usual four movements, it begins with a genial sonata-allegro followed by a downright infectious scherzo with a folk-music feel; one pictures Scots folk dancing on the lawn. A set of variations, again on a folk-like tune, follows; expert indeed, it is infused with both melodic and formal interest. The finale is another sonata-allegro with catchy dotted rhythms, all worked out with impeccable skill and grace. There is even an echo of Schumannesque fugato to be heard. The quartet was written in 1875, so it was probably a bit old-fashioned at the time, but at the distance now of more than 125 years that matters little. This is a piece that demands to be heard. One can only hope that it will be taken up by other groups. The 11-minute Phantasy Quartet (1911) by Frank Bridge (1879-1941) was the third of the pieces Bridge wrote for W.W. Cobbett's annual competition for works in the 'Fantasy' form -- one movement, short duration, variations in tempo and meter. Bridge's work, heavily influenced by the new Impressionist ethos, is rhapsodic with full-throated lyrical melodies and both musing and exultant passages. The Piano Quartet (1917, rev. 1936) of Herbert Howells (1892-1983) is in three movements. Howells, perhaps best known for his gorgeous sacred choral works, also left a large body of instrumental works, among them this quartet which has, unfortunately, never figured heavily in concert programs. Its first movement is a serene folk-tinged ballad. Its second movement, a gentle Lento molto tranquillo, is one of the highlights of this disc. The Ames Quartet play it with ineffable tenderness. I found myself going back to it again and again. The finale is a rumbustious allegro notable for its modal harmonies, evoking a rural Hardyan England. Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924) was an Irish composer and pedagogue (teacher of, among many others, Holst, Vaughan Williams, Bridge, Howells and Jacob). His music is conservative and exceedingly beautifully crafted. He also was a richly talented melodist. The First Piano Quartet (1879) carries strong influences of Schumann and Brahms. It is notable for its high spirits. The sonata-allegro first movement has particularly appealing themes. Amazingly, he tops that with a second-movement Scherzo which bubbles and dances. The Adagio is a plaintive hymn with a gently spirited trio. The finale is a joyous rondo that sounds for all the world like it could have been written by Schumann. The Piano Quartet (1969) by Gordon Jacob (1895-1984) is altogether more dramatic and angular than anything that precedes it in this set. Jacob, known primarily for his band music, as an arranger of others' music and as a writer on musical subjects, was a serious composer with an extensive portfolio of abstract works. Although conservative for his generation, nonetheless the music is strong meat with heavy dependence of secundal, quartal and modal harmonies. Its dramatic qualities are aptly underlined by the performance here. The final work presented here, the Piano Quartet (1922, rev. 1976) of William Walton (1902-1983), was a student work Walton strengthened fifty years later. After a strongly modal first movement the Scherzo, placed second, has echoes of both Debussy and Stravinsky. The real gem of the work is the pastoral third movement, Andante tranquillo, which for all its Impressionist harmonies sounds as quintessentially English as anything written by, say, Vaughan Williams. The finale, Allegro molto, is again Stravinskyan, particularly in its virtuoso piano writing, and features islands of lovely reposeful string writing before reaching an exuberant ending. I cannot praise highly enough the playing of The Ames Piano Quartet -- Mahlon Dartington, violin; Jonathan Sturm, viola; George Work, cello; William David, piano -- whose work here is of the highest order. I had admired their earlier set of the Fauré piano quartets but with this set I realize I need to seek out their other recordings; this is a world-class ensemble. Strongly recommended. Scott Morrison" THE LAND WITHOUT COMPOSERS DAVID BRYSON | Glossop Derbyshire England | 05/02/2007 (5 out of 5 stars) "Time to thank America. If Britain in the 19th and early 20th century gained itself a European reputation as being some `land without composers' that was largely because musical Britain had corralled itself in an enclosure of its own constructing. There were plenty of interesting British composers throughout that period, differing widely in their musical idiom at that, but there was little sense that the British musical culture looked outwards. Boult had long championed his compatriots of course, and more recently the British Piano Concertos series has given an airing to some worthwhile and unfamiliar works thanks to Peter Donohoe. However these artists are themselves English, and Europe never showed much interest, but if Boult has a successor it is none other than Previn; and now here is the Ames Quartet coming to the rescue of some fine British chamber music.

This British insularity showed itself in two ways principally. In the later 19th century the most established British composers were ultra-conservatives -- not conservative in the way Elgar was, but would-be adherents of Brahms who never caught up with Brahms in the first place, such composers as Somervell, Mackenzie and Stanford. The other factor isolating Britain was a suicidal fixation with British folk music and an obsession with rural England, a kind of hedgerows-and-Housman club. No wonder the rest of Europe switched off, but fortunately times change. There is a clear reaction these days against some of the more avant-garde cacophony and experimentation, together with a reawakening of interest in not only music that is comparatively traditionalist and backward-looking such as that of York Bowen, but even in the ultras too. If Mackenzie's quartet here had been played to me without attribution I would have been fairly certain that it was not Bruch being too conservative to be by him, but I would still have thought it was rather good; and now there are fewer censors to tell me not to think that. The only other thing by Mackenzie in my collection is his Scottish Piano Concerto, and nothing could be more striking than how much better Mackenzie composes when, as in this quartet, he relies on his own primary inspiration and shakes off the dead weight of ersatz nationalism. Time now to thank these American players specifically. The Ames Quartet are a first-class ensemble just as executants before we come to their interpretations. The pianist in particular has a firmness of touch that I prefer to the tentativeness of Susan Tomes of the much admired (and justly admired) Domus ensemble. There are six separate works here, varying in idiom from the downright reactionary (Mackenzie and Stanford) to the mildly modernistic (Jacob and Walton). I welcome the selection in the first place for its thoughtfulness and intellectual curiosity, and above all for the Walton item. Walton is a long-standing favourite of mine, and I have a very respectable collection of his work, but this quartet is a new one on me. It rounds off the recital in superb style with a spiky finale that gets some magnificent playing from the instrumentalists. They show understanding and insight into the various styles they have to put across to us, and where lyric warmth is called for, particularly in Mackenzie's piece, their tone is a joy to listen to. Power when called for is effortless and unforced, tempi seem just and affectations and mannerisms are thankfully absent. The recorded sound is up to the high standard that we have been led to expect these days and therefore rightly demand. It would be unreasonable and impolite to demand more productions like this, but if there are going to be any more on offer we should all think ourselves privileged." |

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1

Track Listings (6) - Disc #1